Dasyuromorphia -- Hairy Tails are twitching!

Origins

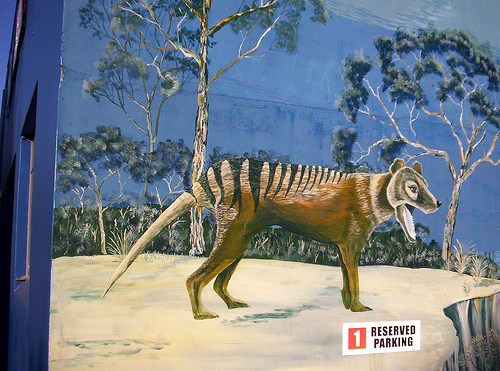

The order Dasyurmorphia (which means hairy tails) consists of most of the most carnivorous marsupials, including quolls, dunnarts, the Numbat, the Tasmanian Devil, and the recently extinct Thylacine. There are three families: one with just a single member, one with only extinct members, including the late "Tasmanian Tiger" (Thylacine - Thylacinus cynocephalus), and one, Dasyuridae, with about 70 members.

The earliest known carnivorous marsupial in Australia, Djarthia murgonensis, comes from the early Eocene (55 million years ago). The taxonomic affiliation of this and two other early carnivorous marsupials is not certain, as key anatomical features used to clearly identify them to family level or even to separate them from the South American marsupial fauna are lacking in the fossils found to date.

The Australian dasyuromorphian and American marsupial taxa are quite distinct but are allied in the possession of many incisors (polyprotodonty) which distinguish them from the herbivorous Diprotodontia. Dasyuromorphians originated in the late Oligocene. The early radiation comprised the very conservative or "primitive" thylacinids. Ranging in size from chihuahua sized, 70 oz (2 kg) to slightly larger than 65 lb (30 kg), thylacines dominated the Australian carnivorous marsupial fauna until the late Miocene, after which they steadily declined to two species present in the Pleistocene and only one persisting until historic times.

Dasyurids first appeared in the fossil record in the early to middle Miocene but were rare until the late Miocene when they diversified and replaced the thylacine as the dominant marsupial carnivore fauna. Most of the Pleistocene fossil dasyurids are from still-living taxa, although none of the living groups occur earlier than the Pliocene. Dasyurids are considered to be highly specialized or "derived" dasyuromorphians in terms of their body type.

The numbats are represented by only one living species which appeared in the fossil record as recently as the Pleistocene. The numbat is a highly specialised dasyuromorphian, with features of the skull, teeth, and tongue adapted for termite feeding.

Physical Characteristics

Unlike herbivores, which tend to become highly specialized for particular ecological niches and diversify greatly in form, carnivores tend to be broadly similar to one another, certainly on the level of gross external form. Just as northern hemisphere carnivores like cats, foxes and weasels are much more alike in structure than, for example, camels, goats, pigs and giraffes, so too are the marsupial predators constrained to retain general-purpose, look-alike forms which mirror those of placental carnivores. The names given to them by early European settlers reflect this: the Thylacine was called the Tasmanian Tiger, quolls were called native cats, and so on.

The primary specialisation among marsupial predators is that of size: prior to the massive environmental changes that came about with the arrival of humans about 50,000 years ago, there were several very large carnivores, none of them members of the Dasyuromorphia and all of them now extinct. Those that survived into historical times ranged from the wolf-sized Thylacine to the tiny Long-tailed Planigale which at 4 to 6 grams is less than half the size of a mouse. Most, however, tend towards the lower end of the size scale, typically between about 15 or 20 grams and about 2 kilograms, or from the size of a domestic mouse to that of a small domestic cat.

Geographic Distribution

This order is represented by two surviving families: the Dasyuridae with 51 members, and the Myrmecobiidae with the Numbat as its sole surviving member. The Thylacine, or Tasmanian Tiger, was the largest Dasyuromorphia and the last living specimen of the family Thylacinidae; however, the last known specimen died in captivity in 1936. The world's largest surviving carnivorous marsupial is the Tasmanian Devil; it is the size of a small dog and can hunt, although it is mainly a scavenger. It became extinct on the mainland some 600 years ago and is now found only in Tasmania. There are four species of quoll, or native cat, all of which are threatened species. The remainder of the Dasyuridae are referred to as 'marsupial mice'; most weigh less than 100 grams. There are two species of marsupial mole — order Notoryctemorphia — that inhabit the deserts of Western Australia. These rare, blind, earless carnivores spend most of their time underground; little is known about them.

Reproduction

Most Australasian carnivorous marsupials are only active at night. Some species, however, have shown occasional periods of daytime activity, and a few species such as the numbat are usually active only during the day. Australasian carnivorous marsupials spend most of their time in the search for food. Each species has different ways of finding prey, from digging for termites, to climbing trees and raiding the nests of possums during the night, to feeding on the bodies of animals that are already dead.

Most Australasian carnivorous marsupials have relatively short life spans. Females usually mate with more than one male, and in many species, offspring born in the same litter have different fathers. Some species in this order only mate once during their lifetime. They usually die soon after reproducing, having used all their energy in a sudden burst of activity required to mate successfully. Antechinus (ant-uh-KINE-us), which are broad-footed marsupial mice, mate in this way. The female lives long enough to raise her young until they can live on their own, but the male often dies before his offspring are mature.

Australasian carnivorous marsupials, like all marsupials, have very short pregnancies, some lasting only days. They give birth to immature young that are usually blind and hairless, and always are unable to survive on their own. In most cases, the young make their way into the mother's pouch, which contains milk teats, and are carried with her wherever she goes. Some species have young that crawl to external teats, or nipples, of the mother. They cling there and are carried wherever the mother goes, protected only by the hairs on her underbelly. Many do not survive to maturity.

The amount of time the young spend growing outside of the mother's womb, or uterus, depends on the species. It can be as short as a few weeks or as long as many months. In most species, once the young have grown enough to fend for themselves, they spend a short amount of time in the mother's nest or den, wandering further each day to find food, until at last they leave the nest for good.

Feeding Habits

Competition for food contributes to differences in foraging niche among all size ranges of carnivorous marsupials that live together, with the exception of the termite-eating numbat but including, historically, the thylacine. Competition appears to be more prevalent in mesic forests and heathlands than in arid environments, where droughts, floods, and unpredictable food supplies may often reduce populations to low levels. Competition from larger antechinus species excludes smaller species from the highest quality habitat, with the result that the smaller species eats smaller prey for which they probably have to work harder. In Tasmania, food competition among the larger carnivores has resulted in separation between species on prey size. If species consume different-sized prey, competition for the same prey items is reduced. Competition has been sufficiently intense over a long enough time scale to drive evolutionary changes in canine tooth size among the quolls. Canine tooth strength, which determines the size of prey that can be killed, have become evenly spaced. Even spacing in prey size among species minimizes competition.

Families within Dasyuromorphia

Videos